When we met, our interest in, and commitment to, biking for transportation was one of the things that Matthew and I shared (along with a love of cooking and eating delicious vegetarian food). Perhaps because of this shared history, it’s particularly frustrating when bicycling becomes a point of contention in our relationship. I’m not talking about, “You spend all your free time riding your bike,” kind of contention, though.

In general, we don’t ride our bikes together all that much. Bike trips to work, or to run errands, are usually solo ventures. Duo trips are limited to weekend (or rare weeknight) outings, so it took a while for us to notice the problems.

Prior to April 2011, the primary point of contention was that I was riding too close to parked cars. I understood Matthew’s concern, but I felt uncomfortable riding farther left in the traffic lane.

Enter CyclingSavvy. We took the basic course together in April 2011, and went on to become instructors two months later. This course gave me the knowledge, confidence, and skills I needed to get out of the door zone and away from the edge of the roadway for good.

It seemed this would be just what we needed for partner cycling bliss.

We do great on multi-lane roads, usually riding two abreast in the right travel lane, then singling up in spots with on-street parking (or other features that narrow the effective lane). But we don’t want to always ride on arterial roads, since there are lower-speed, less-trafficked options, nor do these big roads always serve our destinations.

And here’s the thing. We agree on all the basic principles: 1) follow the rules of movement, 2) practice good communication, 3) never ride within 5 feet of a parked car and you won’t get doored (or startled), 4) never, ever ride up along the right side of a tractor-trailer (or bus, garbage truck, etc.). Those are just a few examples, but suffice it to say, we agree on most things when it comes to how/where we ride.

But then are the “gray areas,” the judgement calls. Where, exactly, on a given roadway do I need to be to encourage safe motorist behavior (i.e., discourage unsafe passing)? When should I actively (or passively) encourage someone to pass me? When should I passively (or actively) discourage passing?

The answer to all these questions is, “It depends.” It depends on road design, traffic conditions, weather, and a number of other dynamics.

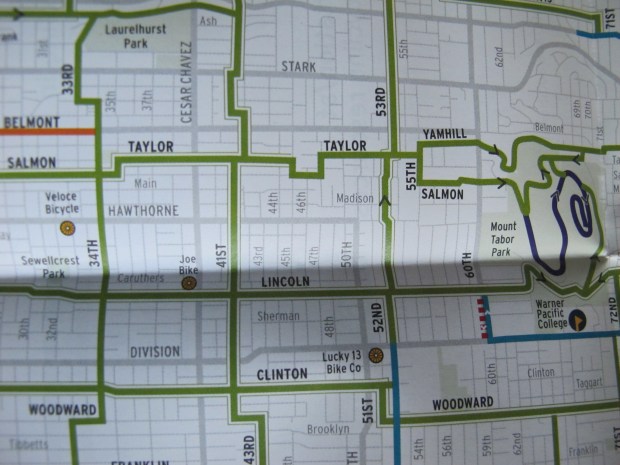

The main north-south route we ride is a tricky one for these questions. It’s a street with two-way traffic, and on-street parking on both sides. Portions of it are too narrow for a center stripe (perhaps just barely wide enough for two cars to eek by each other if there are also parked cars on both sides at a given spot). Other portions do have a center stripe, creating a narrow lane of travel in each direction. The blocks are short, with a stop sign at almost every intersection, so it’s difficult for anyone (motorists or bicyclists) to work up much speed. There are also alleys that exit onto the street in between every intersection, so LOTS of potential turning conflicts.

But it’s a neighborhood street, with low speed limits and relatively little traffic, and it offers an alternative to a traffic sewer (Kingshighway, which we do ride portions of).

We’ve ridden this route for years, and when we’re riding solo, we each navigate this stretch as we see fit.

In general, I move a bit slower on my bicycle (especially when I’m hauling a kiddo), and I tend to look for opportunities to “release” a motorist who ends up behind me, even if it means I need to slow down a bit more to facilitate the pass.

Matthew also practices control and release, but, when on his own, is usually moving a bit faster, meaning less opportunity to release (and perhaps less real need, though there’s still the “Must Pass Bicyclist Syndrome” to deal with). He also tends to ride MORE than five feet from the parked cars, to discourage unsafe passing by both overtaking and oncoming (because the passable street width is so minimal with on-street parking) motorists.*

I prefer to stay closer to the right as a default position on this stretch (though still at least 5 feet from the parked cars, not riding the edge, not weaving in and out of parked cars, etc.), and use active encouragement/discouragement to communicate with motorists about when it is or is not safe to pass. (In truth, I may be cheating in a bit on that 5 feet from parked cars along some of these stretches — we may need to bring out the tape measure on this one, to double check both of our perceived vs. actual distances.)*

Yet what we do almost effortlessly alone, with one bicycle, becomes REALLY difficult when we add the other person and that second bicycle.

- The dynamic changes for Matthew because, in order for us to actually ride together, he’s traveling slower than normal.

- Instead of time and space to pass one bicyclist (it’s too narrow for us to ride two abreast on the streets in question), overtaking motorists need time to pass two bicyclists.

- The front rider (usually me, setting the [slow] pace) needs to decide if it’s safe to encourage a pass, but the rear rider needs to communicate with the motorist.

- On these short blocks, by the time I see a gap, make a decision, and communicate with Matthew, the gap is gone, or we’re at the next stop sign — too late for him to signal the motorist to pass.

So our shared bicycle outings, times where we should be enjoying our common love of bicycle transportation, become fraught with tension, disagreements, and stress. Instead of feeling good, we arrive at our destinations feeling “yuck,” and, for me, at least, wanting to give Matthew a five minute lead on the way home, just so we don’t have to deal with it. And wanting to never ride our bikes anywhere together again.

So we’re taking advice. Do any of you cyclist pairs have suggestions for harmonious partner bicycle travel on roads/in situations like what I describe? Any tricks for clearly communicating with each other on the road?

*Regarding our roadway position, and where we need to be to get safe passes — in our small sample, it seems there may be some motorist bias based on bicyclist’s sex, i.e., motorists behave better around female cyclists than around male cyclists, so Matthew has to ride differently (i.e., farther left) to get the same passing distance I get when riding a bit farther to the right.

![IMG_5821[1]](https://hergreenlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/img_58211.jpg?w=620)